The Village That Moved: A Himalayan Story of Survival

Sandesh Shrestha, January 2025

A Home in the Sky

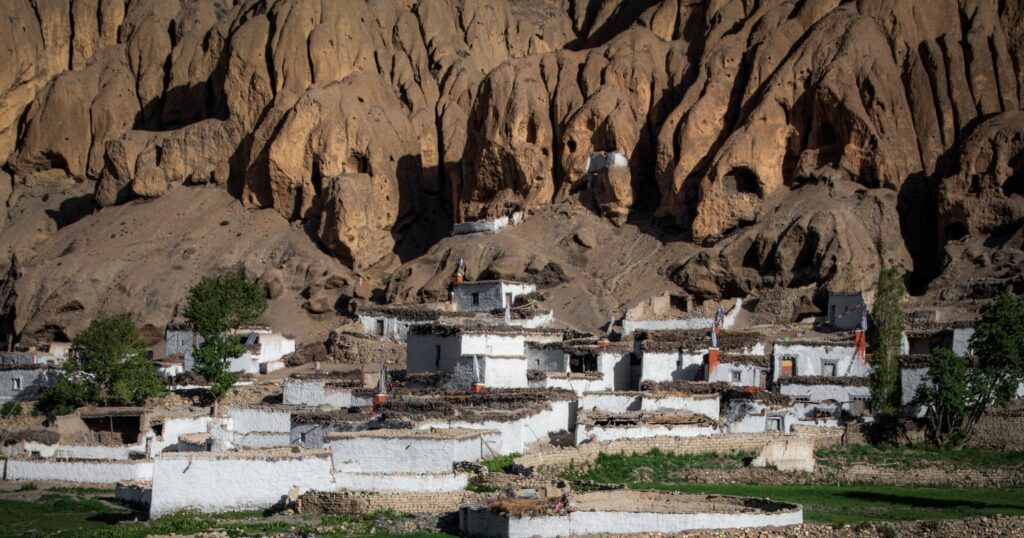

For as long as anyone could remember, the people of Samzong lived in a world few outsiders could imagine. Nestled at nearly 4,000 meters in Nepal’s Upper Mustang region, the village stood defiantly in a stark, windswept landscape of red cliffs and snow-capped peaks. Life was harsh but predictable. The seasons came and went, the glacial stream flowed steadily, and the barley fields turned golden every autumn.

Life was never easy, but it was familiar a rhythm tied to the seasons and the steady flow of a glacial-fed stream that nourished the fields. The villagers prayed to the mountain spirits and believed they would always provide.

But in the late 1990s, the mountains stopped listening. The stream shrank. The rain became erratic. Winter snow, once dependable, grew lighter with each passing year. The land that had sustained them for centuries was slowly abandoning them.

The Water Disappeared

It started subtly the stream that cut through the village’s heart began to run lower than usual. At first, the villagers dismissed it as a temporary drought. They had survived dry spells before. But this time, the water didn’t return.

“Our crops dried up before our eyes,” recalls a village elder. “The fields turned to dust. The earth stopped giving.”

The fields, once rich with golden barley and swaying buckwheat, became cracked and lifeless. Without water, livestock perished, leaving the villagers with little to trade at distant markets. Families rationed what little food they had, stretching supplies to last through harsh Himalayan winters.

When the rains did come, they arrived in violent bursts not gentle showers but destructive storms that washed away topsoil and triggered dangerous landslides. Crops were swept away before they could take root.

“The rain came too late or too much,” says another villager. “It was like the mountains were punishing us.”

The Border That Closed

For generations, the people of Upper Mustang in Nepal lived a nomadic lifestyle shaped by the rugged Himalayan landscape. They herded yaks, sheep, and goats across vast alpine pastures, freely crossing the Nepal-Tibet border in search of seasonal grazing lands. These migrations were essential for survival, ensuring livestock had ample forage even during harsh winters.

However, this way of life came to an abrupt end in the 1950s when China annexed Tibet and sealed the border. What had once been open high-altitude plains turned into a restricted boundary, cutting off the villagers from the expansive Tibetan grazing lands they had depended on for centuries.

“Our grandparents used to take the animals across the mountains,” an elderly resident recalled. “There was always grass on the other side.”

With access to Tibet’s pastures gone, villagers were forced to keep their herds within Nepal’s limited grazing areas. Competition for grass intensified as livestock numbers grew, pushing the fragile rangelands of Upper Mustang to the brink. Disputes over grazing rights flared, sometimes escalating into conflicts between neighboring communities.

Trapped within a shrinking landscape and battling an increasingly unforgiving environment, the people of Upper Mustang faced a harsh new reality: adapting to life without the freedom their ancestors once relied on.

Pressure on the Rangelands

Before the drought, the village’s survival hinged on its high-altitude rangelands, where yaks, goats, and sheep grazed. These animals were essential, providing food, wool, and dung for fuel. However, as water sources dwindled, the already fragile pastures became even more critical and dangerously overburdened.

Desperate to secure food and income, villagers increased their herds despite the land’s declining productivity. This created a destructive cycle: more livestock meant more grazing pressure on already depleted grasslands.

“The more animals we had, the harder it became,” reflected a former herder. “But how could we survive without them?”

The fragile alpine grasses, naturally slow to grow, were grazed down faster than they could regenerate. Bare, eroded patches scarred the mountain slopes, accelerating soil erosion and further degrading the land.

“We were caught between hunger and survival,” explained another villager. “We needed the animals, but the land couldn’t support them anymore.”

The struggle underscored the harsh reality: survival in the unforgiving Himalayan environment hinged on a delicate balance between nature and human needs a balance the changing climate had shattered.

A Village in Crisis

By the early 2010s, survival became a daily struggle. The once fertile fields were barren, the streams that had sustained them for generations had dwindled to a trickle and the pressure on the limited grazing land had reached a breaking point. Crops failed year after year, and food became an increasingly scarce commodity. The villagers realized that their survival was no longer certain. They gathered to discuss their options, knowing that the future of their children was at stake. The decision was not easy. The land, with its sacred sites and ancestral significance, had been home for centuries. Leaving it behind was unimaginable for many.

In desperate need of a solution, the people of Samzong turned to the Lomanthang Management Foundation (LMF) for help. After careful consideration, it was decided that the only viable option was to relocate the entire village. A new site, located on the left bank of the Kali Gandaki River, about 8 kilometers southwest of the original village and 4 kilometers northeast of Lo-Manthang, was chosen. This area, named Namashung, offered more reliable water sources and better prospects for agriculture.

The land for cultivation, a plateau bordered by the Kali Gandaki to the west, was generously granted to the community by the former King of Lo. This move provided a glimmer of hope, but the emotional cost of leaving their ancestral home was still a heavy burden. Despite the promise of a new beginning, the villagers faced the heartbreaking reality of abandoning the land that had sustained them for generations.

Starting Over

The move was as difficult as the villagers had feared. With no roads leading to the new site, they had to carry everything themselves cooking pots, blankets, farming tools, and sacred religious relics. What they couldn’t carry, they left behind.

Despite the challenges, the villagers were determined. They came together, working as one to construct their new lives. They built homes, cleared fields, and planted crops, relying on their strength and resilience to create a new foundation. While the economic support from donors helped with some of the material needs, it was their own hands and hearts that shaped the new village.

In July 2018, when fieldwork was conducted, many villagers were still in the process of moving. By 2019, the move was completed, and they had settled into their new lives, though the challenges of rebuilding continued.

What Was Lost

They left a way of life that had been passed down through generations. Samzong’s high-altitude terrain shaped its people, their traditions, and their deep connection to the land. The fields they once cultivated were not merely a source of sustenance they were woven into the fabric of their identity. Seasonal rituals and gatherings at sacred sites marked the flow of life, binding the community to each other and to their surroundings. The relocation severed these ties.

The move to the new site brought tangible benefits: better access to water, improved infrastructure, and the promise of a more secure future. Yet it also came with profound losses. The new village offered no substitute for the spiritual and cultural significance of Samzong’s historic landmarks. The communal spaces where stories were shared, and bonds were strengthened were replaced by a foreign setting that felt unfamiliar and detached.

For the elders of Samzong, the loss was particularly poignant. They carried the weight of memories tied to the land the planting and harvesting of crops, the shared struggles during harsh winters, and the view of the rugged mountains that had watched over them like silent guardians for centuries. For the younger generation, the relocation created a tension between embracing new opportunities and preserving the traditions of their ancestors.

A Warning from the Mountains

The relocation of Samzong is more than a story of a village forced to move it is a grim foreshadowing of the changes sweeping across mountain communities worldwide. The fate of Samzong serves as a chilling reminder of the vulnerabilities faced by communities at the frontlines of climate change. In mountain regions, where life is already precarious, even small shifts in temperature or precipitation can upend centuries-old ways of living. Samzong’s story echoes the struggles of countless other highland villages around the world, where communities are grappling with the same relentless forces.

Beyond the human cost, the relocation of Samzong highlights the broader ecological impacts of climate change. As glaciers shrink and ecosystems shift, downstream regions are beginning to feel the ripple effects. The disappearance of mountain water sources not only threatens isolated villages but also imperils the millions who depend on these resources far beyond the peaks.

Samzong’s story is a warning, not just for mountain communities but for the world at large. It underscores the urgent need to address the root causes of climate change while also preparing for its consequences. The mountains, often seen as timeless and unchanging, are speaking. Will we listen before more communities like Samzong are forced to leave behind the lands that have defined them for generations?

As the people of Samzong rebuild their lives in a new location, they carry with them both the scars of displacement and the resilience of their ancestors. Their story is not just one of loss but of adaptation and hope a reminder of humanity’s capacity to endure. Still, their voices call out as a warning from the mountains: if the world does not act, many more will face the same fate.

Author Sandesh Shrestha is currently working as a forester and remote sensing specialist at Aster Global Environmental Solutions, USA. This article is based on research conducted during the summer of 2018 as part of his master’s studies at University of Maine, USA.

The Village That Moved: A Himalayan Story of Survival Read More »