A Report from “Mountains in the Changing World”

Posted on November 25, 2017

For this month’s story, we have a special report from a recent conference held in Kathmandu that SmartPhones4Water had the honor of participating in. It was written by two hard-working and creative young scientists on staff with S4W-Nepal who were able to attend the conference. We hope you enjoy!

George Bernard Shaw once said that if you exchange the same number of apples with someone else, the number of apples you have won’t change. However, if you exchange same number of ideas with someone else, your ideas will double. With the goal of providing a forum for exchanging ideas, research findings, and knowledge related to various aspects of mountains, their unique ecosystems and environment, and how we as humans interact with and affect them, the second international conference on “Mountains in the Changing World” (MoChWo) was held on October 27th and 28th of this year at The Radisson Hotel of Kathmandu in Nepal. It is an annual event organized by the Kathmandu Institute of Applied Sciences (KIAS), and it is attended by many national/international scholars, researchers, policy makers and students. SmartPhones4Water staff and volunteers had the opportunity to attend and participate in this important conference.

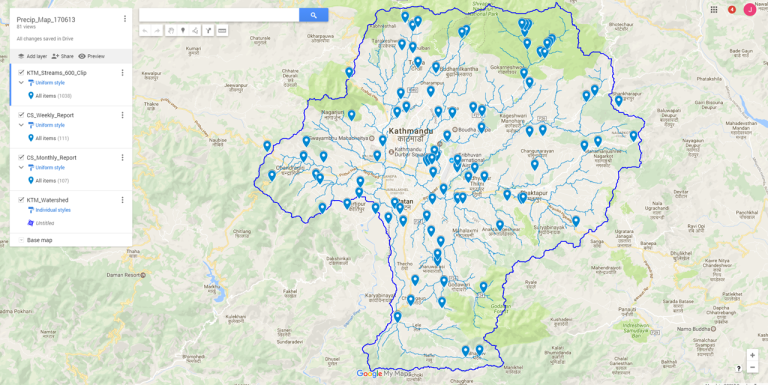

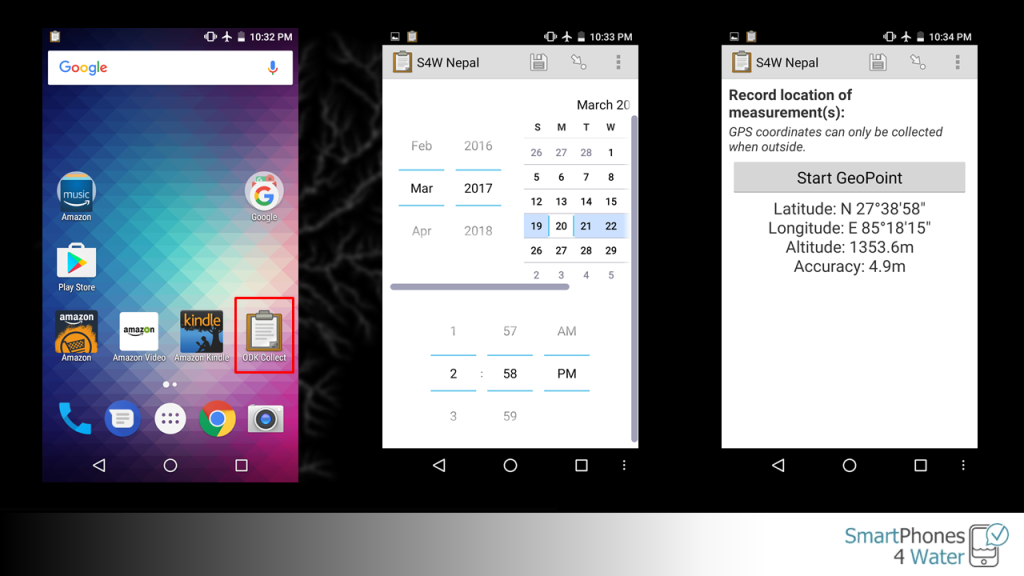

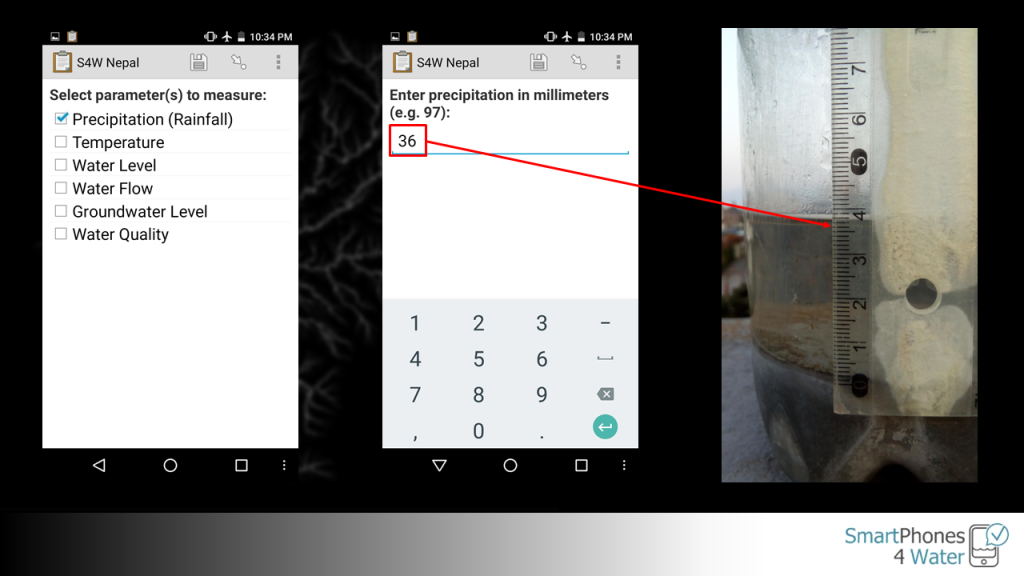

The major theme of MoChWo 2017 was “Air Pollution: Mechanisms and Consequences”. However, it also covered a broad range of other topics including disasters, biodiversity conservation, climate change, environmental pollution, forest management, soil, water and atmospheric research, agriculture and agro-ecology, and sustainable livelihood. The presentation of these topics are covered through four symposiums and a poster presentation session. Smartphones4Water Nepal (S4W-Nepal) was mainly involved in “Citizen Science for a Sustainable Mountain Future” symposium which aimed in understanding the essence of applying citizen science in several topics of research to generate critical environmental data. Another focus of the symposium was on combining citizen science with low cost technologies for implementing citizen science projects in Nepal. One major noteworthy result of this symposium was the establishment of the Citizen Science Association of Nepal (CSAN). This brings all national organizations, researchers, policymakers, and students working with citizen science together under one umbrella.

S4W-Nepal provided 17 scholarships to student researchers (which covered either partial or full conference registration fees) through a competitive process based on qualitative evaluation of abstracts the students had written about their research. Similarly, an independent award evaluation committee led by Dr. Rashila Deshar evaluated all oral presentations and posters presented by students. As a result, four best awardees were awarded with certificates and a token of love. Ms. Anusha Pandey, one of our S4W-Nepal staff members, won best undergraduate oral presentation award! 🙂

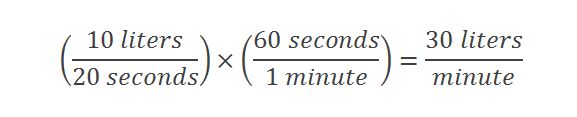

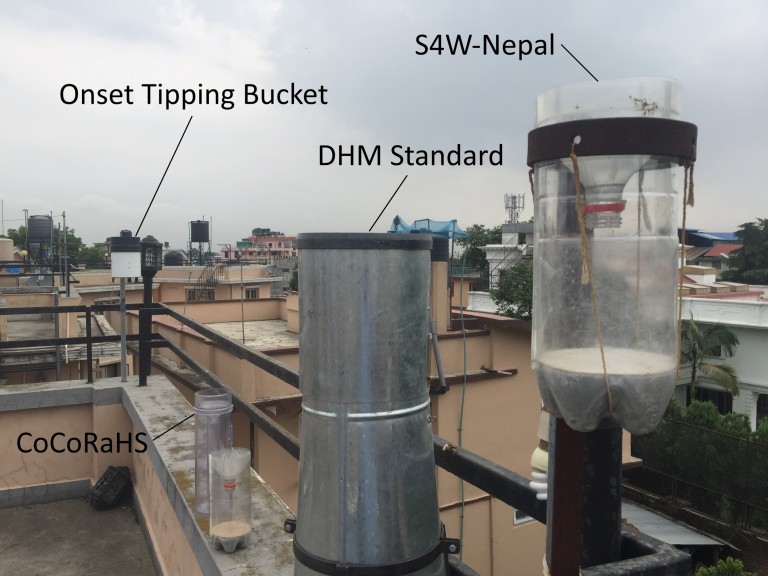

Her presentation was on the evaluation, identification, and implementation of the most plausible flow measurement technique for citizen science.

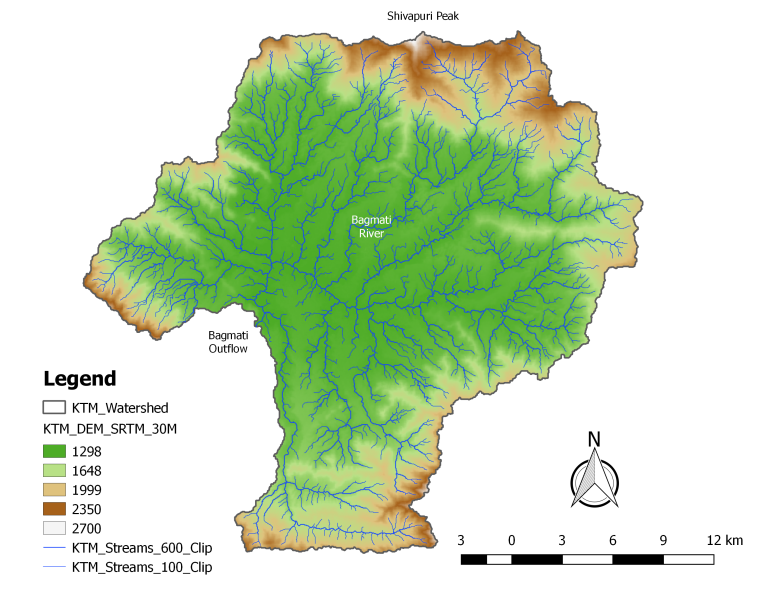

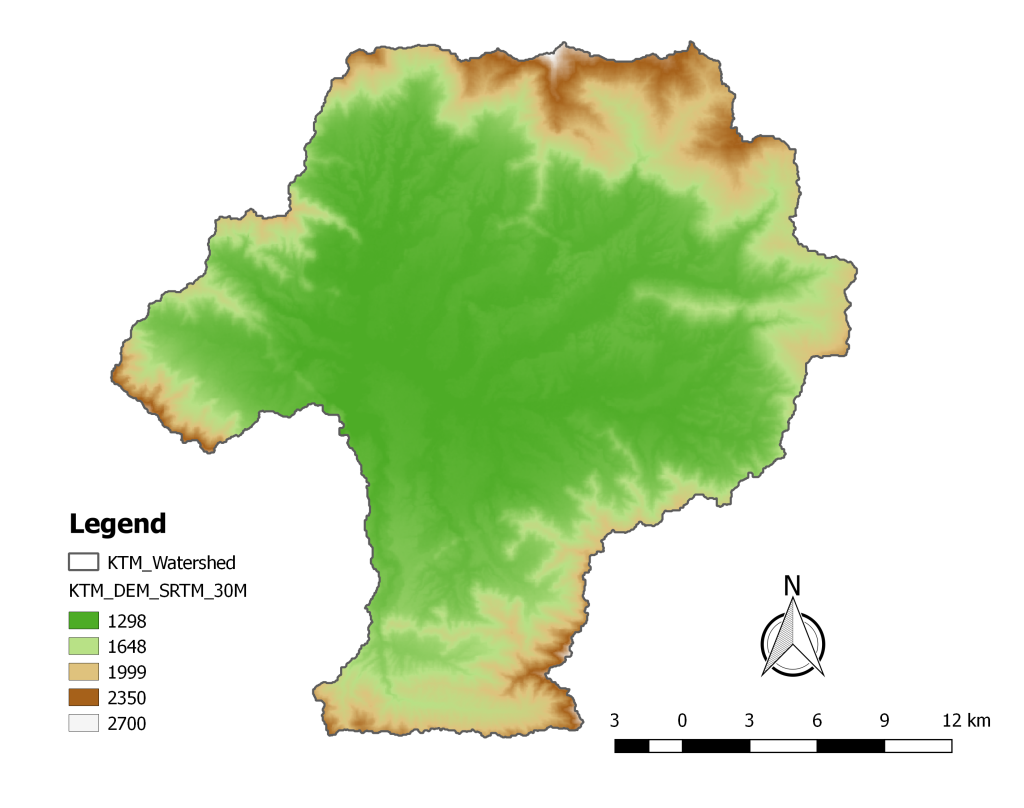

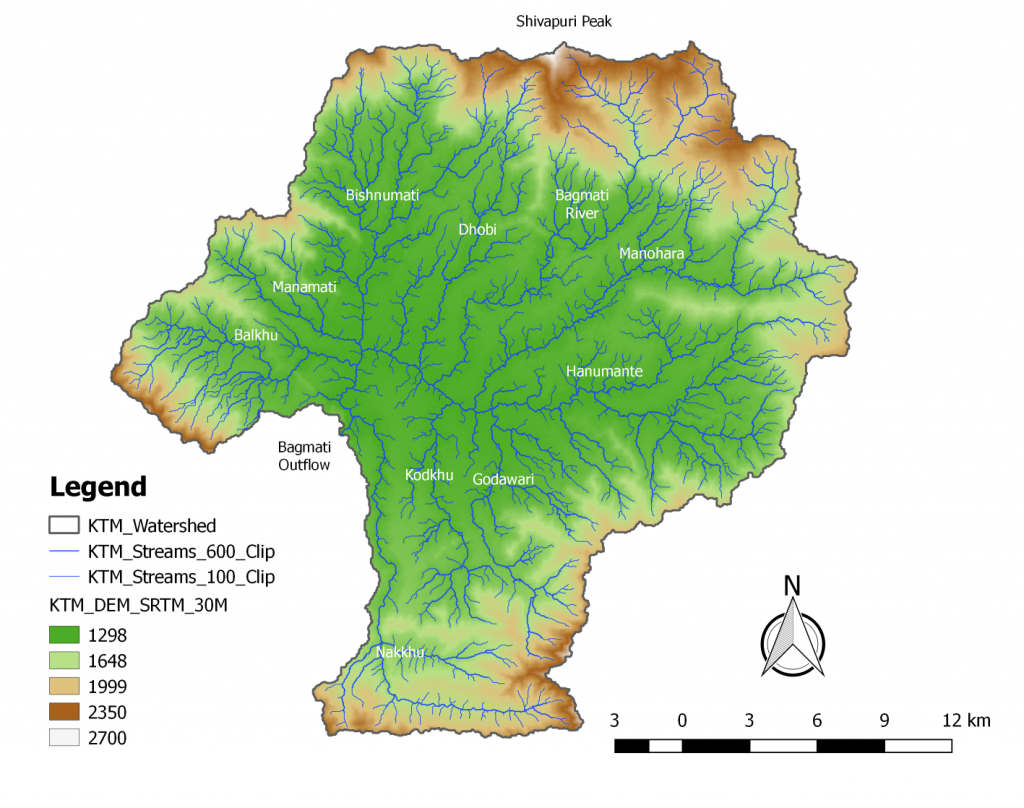

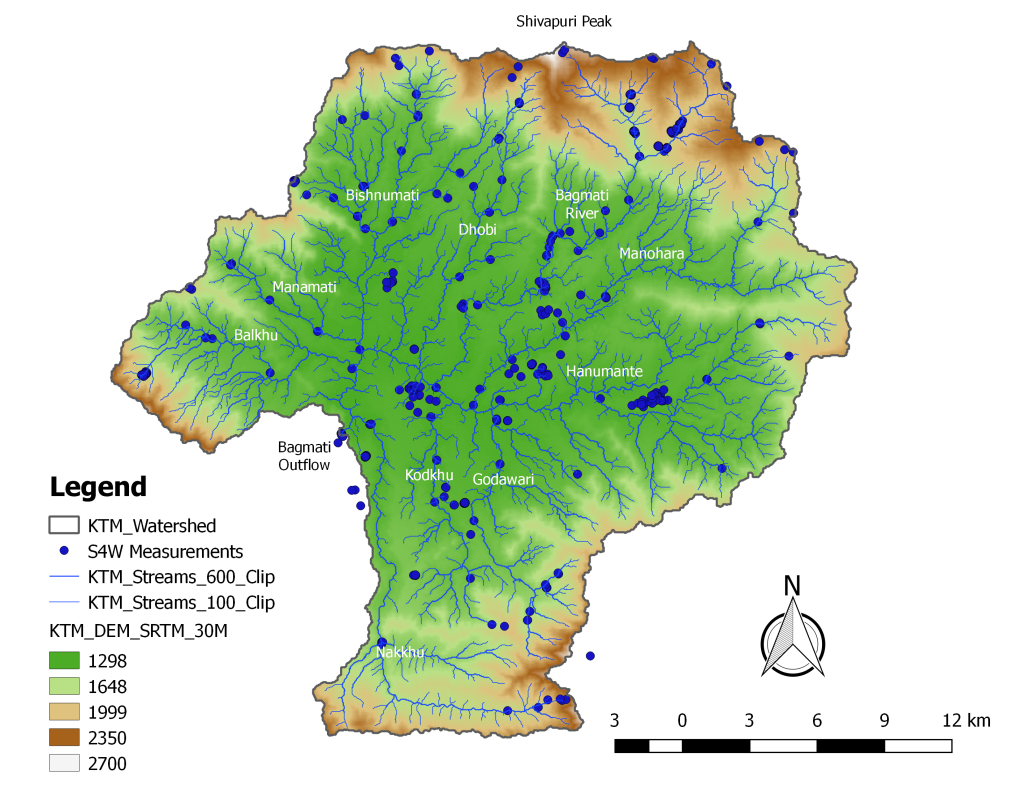

Two members of S4W-Nepal’s advisory board, Dr. Steve Lyon (Professor of Department of Physical Geography from Stockholm University, Sweden), and Dr. Ram Devi Tachamo Shah (Project Coordinator, Aquatic Ecology Centre, School of Science, Kathmandu University), chaired the “Citizen Science” symposium. Dr. Steve gave a presentation about connecting hydrological modelling to stakeholder participation and Dr. Ram Devi on sustainable approaches for biomonitoring of water bodies. Additionally, some of our friends from TU Delft, Netherlands gave a presentation about the influences of land use on the quantity and quality of water sources inside Kathmandu Valley, including a discussion of utilizing citizen science in the future to help collect the data that they collected and used for their study.

Overall, the conference was a very productive two days of a variety of people from diverse backgrounds and interests coming together to discuss ideas, projects, and research in our beloved home country of Nepal. All of us from S4W-Nepal were honored to be a part of the conference and have the chance to bring some of our own apples to share with others, and we’re pleased to report that George Bernard Shaw was right. We left with more apples than we came with.

By Anusha Pandey and Anurag Gyanwali